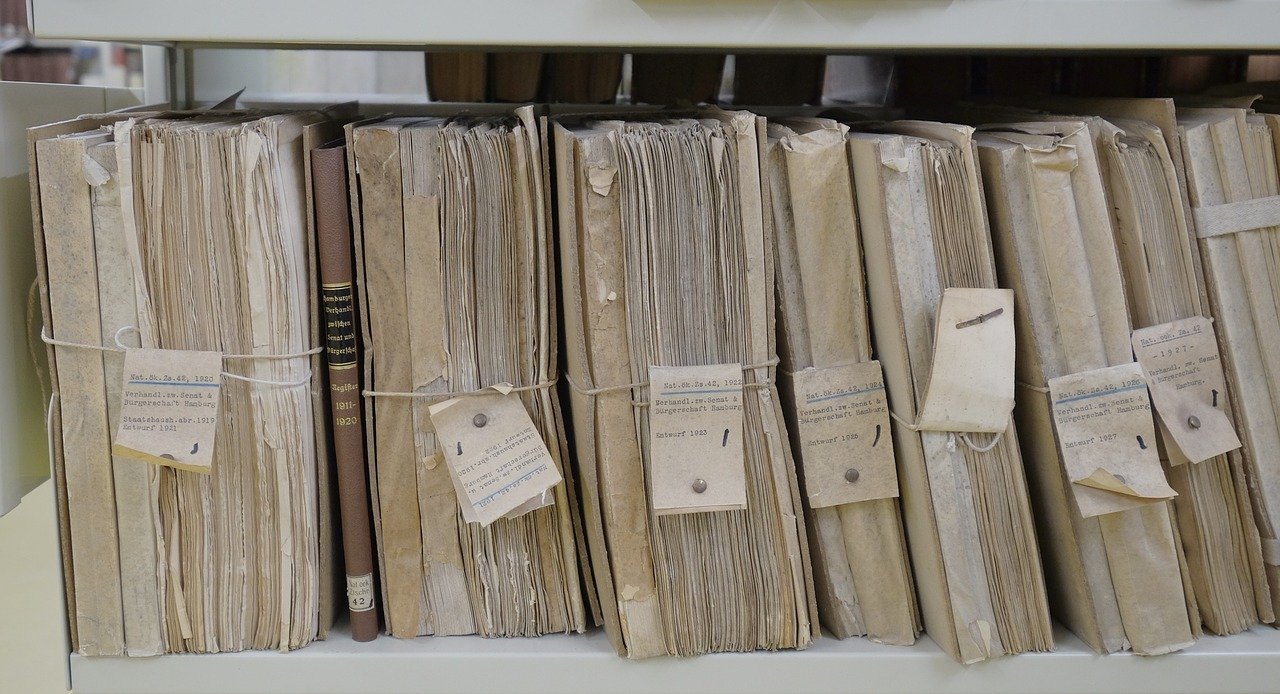

Following a request from Rev. Linda and Sally Taylor, for the past six months Sandy Brooks and I have been volunteering to spend a couple of hours most weeks in the bowels of the church where the old boiler room has been converted to the Archives Room. We’ve enjoyed the sorting and organizing work involved, and there is still much to be done. However, during the “Story” theme we took up in worship services this month, Rev. Linda threw out a challenge to the congregation about doing more work on unearthing little-known or rarely told stories from our church history.

In response, in a letter to Sally and Rev. Linda, I described the distinction between archival work and archival research. As we have undertaken our sorting and organizing tasks since December 2020, Sandy Brooks and I have only incidentally considered the possibilities for archival research. Archival research is what Rev. Linda was imagining when she referenced in a sermon her hope that we can come up with a better record of the important stories that shape the history of the church. To create such stories, there are several steps in archival research:

- Decide what stories you think are most important to tell, or which people are most important to document, or which blocks of time you want to describe. Each of these options gets you started on searching for information. Each of them brings a point of view or expectations that you have to be open to having challenged or changed by what you find.

- Find in the archive whatever is there related to the story, the person, or the era in time that would want to describe.

- Start to piece together the narrative (the story) that can be told.

- Interview any members who are still here with first-hand knowledge of that story.

So often in any historical research, we tend look first to the conflicts, because those are the most interesting stories for most people. The conflicts often involve social justice issues, leadership mistakes or failings by ministers or lay leaders, or cultural/political events to which the church was responding. Focusing only on those things can miss other important stories or people that don’t immediately come to mind when you tell a capsule history of the church: for example, important lay leaders and donors whose commitment over time provided a firm foundation for the church to survive and thrive; decisions about property acquisition or sale; the changing culture of the church through stories about how we taught our children about religion; how we played and celebrated; how we worshiped.

The archivist at Meadville Lombard Theological School in Chicago has done a great job of taking up a theme and creating displays in the main meeting room of the school that illustrate stories from the school’s history over time. He will include photographs, short essays representing original research to read and original documents in a display. On a modest scale, this is what museum curators do. Possibly as we consider the uses of the church foyer and of the Jeffersonian interpretive material and memorabilia we have, we could consider other forms of historical display that tell our stories. It would be a challenging but enjoyable job for archives volunteers in the future, going beyond the more mundane tasks of sorting and filing documents.

Wayne Arnason